Forged by Crisis: How External Shocks Reshape Societies and Drive Technological Change — Exploring the Case of Japan

External shocks — the Cuban Missile Crisis, Black Death, OPEC Embargo, WWII, and Perry’s arrival in Japan — forced lasting political, economic, and technological transformations.

This reading is part of a series:

Powering the Rising Sun: Japan's Quest for Energy Security in the 20th Century

Turning Points

History offers many examples of societies, when confronted by sudden shocks, being compelled to abandon their resistance to change and embrace uncharted courses. These shocks, sometimes seismic in their impact, reshape the trajectory of nations and cultures.

Cuban Missile Crisis: A Turning Point for Arms Control

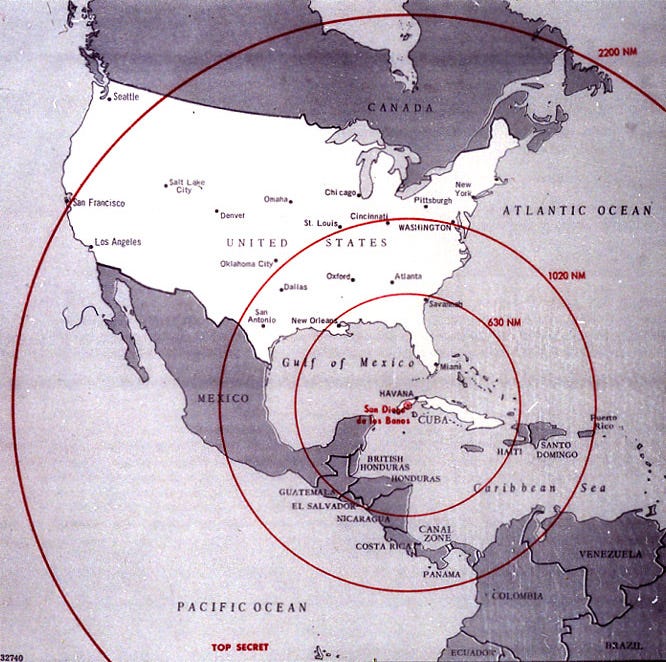

The Cuban Missile Crisis stands as such a moment — a dramatic confrontation that forced the U.S. and the Soviet Union to reconsider their nuclear ambitions. For 13 tense days, the world teetered on the brink of annihilation when the US discovered that the Soviet Union had secretly installed nuclear missiles in Cuba, just 90 miles off the coast of Florida. In its aftermath, the superpowers, newly awakened to the apocalyptic potential of nuclear conflict, adopted fresh diplomatic strategies, including arms control agreements, which sought to prevent the unthinkable.

Black Death Setting the Stage for the Renaissance

Perhaps even more transformative was the Black Death, which ravaged Europe in the mid-14th century. Sweeping through the continent via trade routes, the plague claimed a third of the population, triggering a demographic collapse that unraveled the social fabric. Labor shortages empowered the working class and disrupted established wealth structures, while the Church, powerless against the disease, saw its authority wane. In this void, a new spirit of inquiry and secular thought began to flourish, setting the stage for the Renaissance — a profound reawakening of art, culture, and intellect that had once been inconceivable in the religious orthodoxy of medieval Europe.

The 1973 OPEC Oil Embargo: A Catalyst for Energy Conservation and Environmental Awakening

In 1973, OPEC imposed an oil embargo on nations perceived as supporting Israel during the Yom Kippur War. This sudden and severe shock to the global oil supply sent ripples through the world economy, particularly affecting Western nations heavily dependent on imported oil. The sharp spike in energy prices and widespread shortages forced governments, businesses, and consumers to rethink their energy policies and consumption practices. What had once seemed stable and reliable — the steady flow of affordable oil — was suddenly in crisis, compelling nations to adopt energy conservation measures, a shift previously unimaginable.

In response to this external shock, many countries introduced policies promoting fuel efficiency, such as the U.S. Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, and accelerated the development of alternative energy sources, including solar, wind, and nuclear power. The crisis also spurred innovations in energy-saving technologies, from more efficient cars and appliances to better home insulation, fundamentally reshaping the energy landscape.

The embargo not only altered energy policies but also gave a significant boost to the environmental movement. While environmental concerns had gained traction in the 1960s, the urgency created by the oil crisis highlighted the vulnerabilities of relying on fossil fuels, linking energy use with environmental degradation and geopolitical instability. The shock of the embargo fueled a new wave of energy-conscious thinking, with conservation becoming a key part of the environmental agenda.

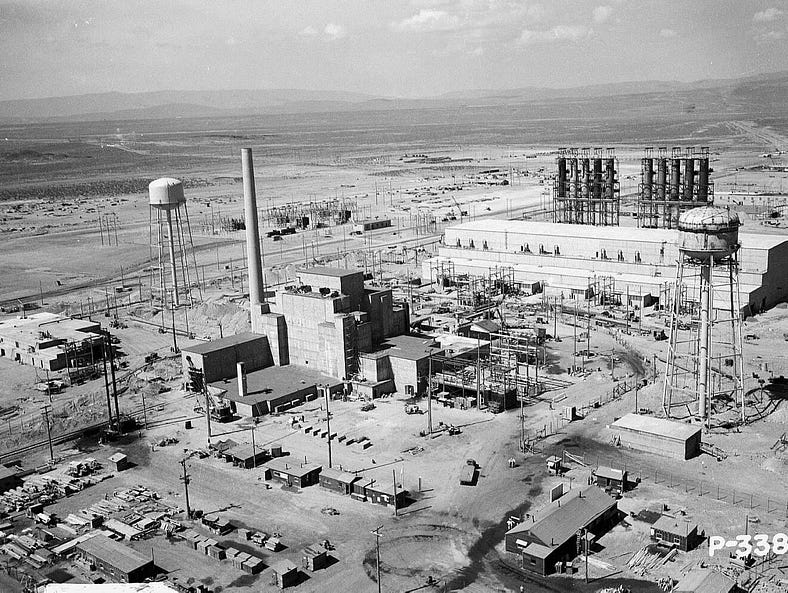

How WWII Accelerated Nuclear Power

The development of atomic bombs likely would not have occurred as early had it not been for the threat of Nazi Germany’s potential nuclear ambitions. The U.S., spurred by this urgent fear, embarked on the massive Manhattan Project with the goal of developing the bomb before the Nazis could. Without this wartime urgency, it’s likely that both the atomic bomb and nuclear energy would have been delayed significantly. At the time, energy resources, particularly fossil fuels, were abundant, and there was little economic or strategic incentive to explore nuclear energy as a primary power source.

When nuclear energy was eventually adopted, it was heavily framed as a symbol of peace and progress. This narrative was essential in post-war efforts to distance atomic power from its devastating military use. Programs like President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” in the 1950s emphasized the peaceful potential of nuclear technology, showcasing its application for energy generation and medical advancements. Its early adoption, therefore, was not driven by immediate energy shortages, but rather by the desire to demonstrate a positive and peaceful use of this powerful new technology — one whose development had taken a giant leap forward due to the exigencies of World War II.

Then there is Japan…

Before 1850, Japan had long remained wary of foreign influence, fearing it would shatter the delicate balance of its social and political order, maintained for centuries by the Tokugawa shogunate that had ruled Japan since the 1600s.

To safeguard this fragile structure, the shogunate had enforced a stringent policy of isolation, restricting foreign contact to a few tightly controlled exchanges with the Dutch and Chinese. Beneath this policy lay a deep-seated fear: that foreign ideas, especially Christianity and Western philosophies, could dissolve Japan’s rigid class divisions — separating samurai, peasants, artisans, and merchants.

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, this isolation insulated Japan from the monumental upheavals of the Industrial Revolution, which had transformed Europe. The shogunate, consumed not with steam engines or factories but with the shadow of Western encroachment, saw industrialization as a gateway for foreign influence — an even graver threat than the technology itself. By the mid-19th century, however, external pressures mounted, exposing a harsh truth: Japan, shielded for so long, stood vulnerable in a world that had outpaced it. The shogunate quickly grasped that it was ill-equipped to fend off the advances of technologically superior Western powers.

Japan’s leap into industrialization was not the product of a slow evolution, but a swift, reactive shift spurred by this external shock. Let us delve into how this seismic transformation unfolded.

Whaling Across the Pacific and How the Hunt for Oil Brought U.S. Whalers to Japan’s Shores

Before electricity lit the night and crude oil powered engines, whale oil was a highly valued commodity. Known for its versatility, it was an essential lubricant in the fast-growing industrial age. As industry expanded in the United States and Europe, whale oil kept machinery running smoothly. It was vital to steam engines and textile mills, helping to drive progress. Outside the factories, whale oil provided clean, reliable light, free from the smoke of lesser fuels. It became essential for lighthouses, street lamps, and homes alike.

From 1820 to 1860, America reigned supreme over the whaling industry, a period known as the “Golden Age of Whaling.” By the 1850s, the United States had reached the zenith of its whaling power. Out of the 900 whaling vessels scouring the oceans, 700 hailed from American ports. These ships, driven by the relentless demand for whale oil, hauled in a staggering 500,000 barrels a year. The whalers, hardened by their perilous trade, ventured farther into the wild seas, their sights set on distant horizons teeming with the promise of fortune (Moment, 1957).

Whaling expeditions were grueling, multi-year odysseys that demanded extraordinary endurance. Voyages often spanned three or four years, covering vast swaths of the North and South Atlantic, and extending deep into the unexplored reaches of the Pacific. These were not mere hunts; they were high-stakes business ventures. A voyage was deemed successful only when the ship’s hold overflowed with barrels of precious oil.

But the quest for whale oil came with immense risks. Whalers faced treacherous waters, savage storms, and the peril of a shipwreck. Yet, driven by the lure of profit, they pressed on, harvesting from the richest waters until they were depleted beyond recovery. As one fertile whaling ground was exhausted, the hunters were forced ever further from home, pushing deeper into the unexplored and unforgiving oceans.

A stark example of this relentless pursuit unfolded in the whaling grounds north of the Bering Strait. In 1849, 50 whaling ships harvested over 500 bowhead whales. By 1850, that number had soared to 2,000, and by 1852, 220 ships were scouring the region, killing 2,600 whales. The scale of this extraction was catastrophic — within a few short years, nearly a quarter of the bowhead population had been wiped out. Due to overexploitation, by 1853, the catch had already dropped by a third compared to the previous year. In response, whalers turned their gaze southward to the Sea of Okhotsk, near Japan’s shores. Between 1845 and 1857, around 15,000 bowhead whales were slaughtered in these waters (Bockstoce, 1995; Demuth, 2020; Vaughan, 1984).

Thus, American whalers, driven by insatiable demand, ventured to the farthest reaches of the earth. The chase for whales became an obsession, a maddening pursuit reminiscent of Captain Ahab’s relentless hunt for Moby Dick. These men scoured desolate seas, chasing whales across the vast Pacific, losing sleep, losing reason, all in pursuit of the elusive oil. The inevitable end of this reckless quest brought them to the shores of Japan — another frontier breached, another world disrupted.

Westward Expansion in America Shifted Japan’s Strategic Role in the Pacific

Amid the ceaseless hunt for whales that churned the seas, the 19th century in America saw a parallel surge westward — a tide of pioneers sweeping across the frontier. New territories were claimed through purchase and conquest, as caravans of settlers trudged over rugged landscapes, following the Oregon and California Trails, eyes set on the promise of new beginnings along the Pacific coast.

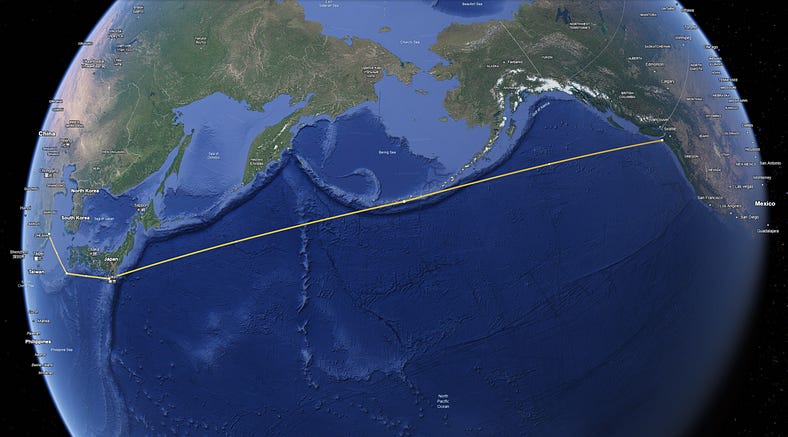

As the West swelled with life, the nation’s ambitions grew bolder, turning ever further toward the vast, untapped riches of the Pacific. The promise of Asian trade, particularly China’s sprawling markets teeming with opportunity, beckoned America’s ships into uncharted waters. No longer driven solely by the pursuit of whale oil, these vessels now sought the spoils of global commerce, carving new paths through the ocean’s expanse. The Great Circle route skimmed the edges of Japan — a nation long veiled in mystery, sheltering itself from the prying eyes of the world.

With the rise of coal-powered steamships, the rules of the sea changed. No longer at the mercy of fickle winds, these iron leviathans cut swift and direct paths across the ocean. For American vessels navigating the desolate, often treacherous waters of the North Pacific, Japan’s islands emerged as a vital lifeline, offering fuel and provisions to crews weary and weather-beaten from their journey.

But to the Japanese, these foreign ships were harbingers of a looming intrusion. For centuries, Japan had jealously guarded its isolation, steadfast in its refusal to entangle itself with the chaotic world beyond its shores. Yet with each American ship that crested the horizon, the fortified walls of seclusion began to quiver — a slow, unsettling reminder that the world outside was closing in, ship by ship, moment by moment.

Commodore Perry’s Arrival Forced Japan to Embrace Modernization

When Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the U.S. Navy landed on Japan’s isolated shores in 1853, his arrival was far more than a diplomatic gesture. Dispatched under the direct orders of the U.S. President, Perry’s mission carried the weight of a burgeoning empire’s ambitions. His stated objectives — securing humane treatment for shipwrecked sailors, establishing coal supply stations, and opening Japan to foreign trade — concealed a more ominous undercurrent. Perry did not offer dialogue but spectacle: a show of force wrapped in the guise of negotiation, executed with the confidence of a naval power well-versed in the theater of domination. His “Black Ships” loomed like iron harbingers of fate, their cannon muzzles speaking more loudly than any word. The demands that followed were less pleas from an emissary than the proclamations of a conqueror.

In the shadow of these imposing vessels, Japan’s two centuries of seclusion began to tremble. The proud, ancient nation stood not at a crossroads, but at a breach — its walls of isolation groaning under the pressure of a new era.

Perry’s visit shattered Japan’s isolation, with other Western powers — Britain, Russia, France — quickly following, eager to exploit the vulnerable nation. The treaties Japan signed became shackles, as sovereign choice faded beneath the unrelenting force of foreign ambition. Perry’s arrival heralded the end of secluded kingdoms, and Japan’s leaders understood that to resist was to risk annihilation.

Industrialization was no longer a choice but an existential necessity. China’s fate, exploited by foreign invaders, loomed as a dire warning, and Japan recognized that modernization was the only path to avoid subjugation. The Meiji leadership launched a rapid modernization campaign, fully aware that survival hinged on embracing industrial power, even at the cost of centuries-old traditions.

Within decades, Japan transformed from a vulnerable target to a regional power, rising not as a victim of imperialism but as a nation with its own imperial aspirations. This remarkable resurgence, born out of the threat of destruction, left Japan indelibly marked by Perry’s arrival. The memory of the “Black Ships” lingered like a distant thundercloud, a reminder that the pursuit of power, once ignited, could never be fully extinguished.

Japan Transformed from Agrarian Society to Industrial Power in a Few Decades

Under Meiji rule, especially after 1885, Japan underwent a remarkable transformation — from a primarily agrarian society to an industrial power capable of competing with the Western world.

When Commodore Perry arrived in the mid-19th century, Japan’s economy was still predominantly agricultural, resembling Western Europe two centuries earlier. Yet, by the close of the 19th century, agriculture’s share of the national output had fallen to less than half, giving way to modern industries that would build the foundation of a resurgent Japan.

This shift was more than an economic revolution — it was the stirring of dormant forces within the nation. Coal replaced wood, steam replaced muscle, and machines replaced hands. The fields emptied, the factories filled, and what once seemed distant possibilities became the engines of progress.

As Japan surged into modernity, light industries like textiles gave way to steam-powered railroads and the production of heavy industrial goods such as chemicals and motor vehicles. With every shift, with every step, Japan advanced along the path of technological mastery. Rising efficiency, falling costs, expanding markets, and deepening expertise drove the nation forward, steadily propelling it toward capital-intensive industries and cementing the foundation of its modern economy.

The Drive to Modernize was Fueled by Japan’s Military Imperatives and National Security

The driving force behind Japan’s rapid transformation was not solely economic ambition. The looming threat of foreign dominance, vividly symbolized by Commodore Perry’s arrival, seared itself into the national consciousness, burned into the fabric of the nation, etched into the minds of its leaders. Japan’s leaders understood that to preserve sovereignty and stand against Western powers, modernization was essential — not only economically, but militarily.

The initial industrial drive was therefore aligned with defense needs. Industries tied to shipbuilding, armaments, and warfare were prioritized. A strong military wasn’t just protection from invasion; it was key to Japan asserting itself globally, both diplomatically and economically. In the harsh reality of international relations, strength enabled equal negotiation; weakness led to marginalization.

Japan’s leaders understood that producing ships, weapons, and advanced technology was the hallmark of a world power. To catch up with the West, Japan had to embrace these industries, reshaping society to face both foreign threats and domestic challenges.

References:

Bockstoce, J. R. (1995). Whales, ice, and men: the history of whaling in the western Arctic ([1st ed.]). University of Washington Press.

Demuth, B. (2020). Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait (First published as a Norton paperback). W.W. Norton & Company.

Jansen, M. B. (2002). The Making of Modern Japan. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Moment, D. (1957). The Business of Whaling in America in the 1850’s. The Business History Review, 31(3), 261–291.

Vaughan, R. (1984). Historical survey of the European whaling industry (Arctic Whaling: Proceedings of the International Symposium, pp. 121–145). University of Groningen.