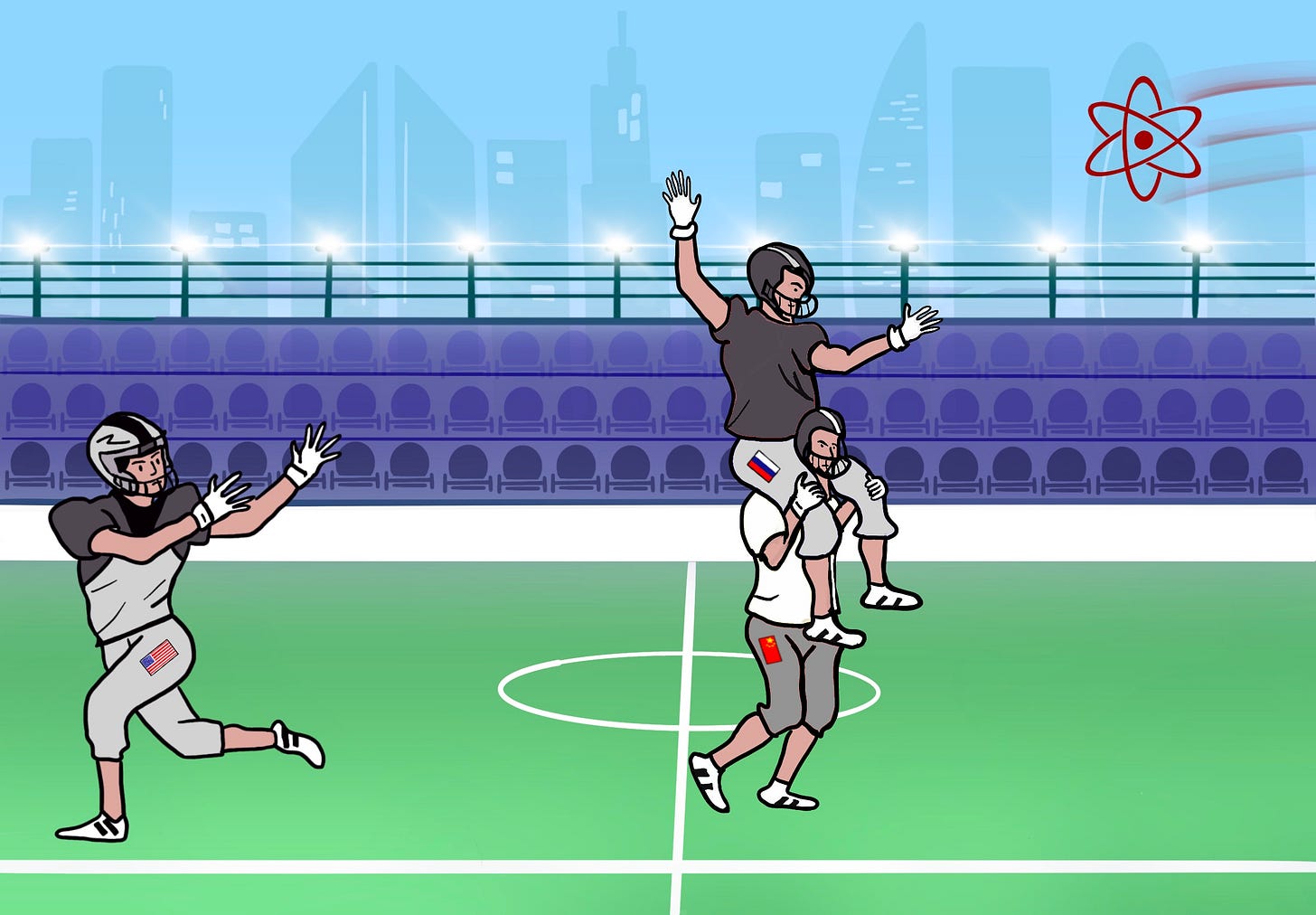

Highlighting America’s Dependence on Foreign Uranium Sources

The U.S. nuclear industry faces a critical dependence on foreign fuel, as Russia, China, and their allies dominate uranium supply and enrichment, raising urgent energy security concerns.

The Quiet Revolution in Nuclear Energy

The nuclear industry is undergoing a tectonic shift—one that few outside the field truly recognize. Today, nuclear energy enters discussions mostly due to AI or its critical role in achieving net-zero emissions. AI companies favor it for its ability to provide firm, round-the-clock power, making it ideal for data centers. As a result, they are investing in next-generation Small Modular Reactors that can be placed directly next to their facilities, bypassing the grid entirely. Others view it as a key stabilizer for intermittent wind and solar energy. Few, if any, discuss it in the context of energy security. Even fewer acknowledge the West’s heavy dependence on Russia for fueling nuclear reactors.

What Does It Take to Produce Nuclear Fuel?

Nuclear fuel production has long been shrouded in secrecy due to its technological overlap with atomic bomb manufacturing. Preparing uranium for use in reactors involves three key steps before it can be fabricated into fuel pellets, which are then assembled into fuel rods.

First, uranium must be mined. This can be done through traditional open-pit and underground mining, as seen in Canada, or via the newer in situ leach method, where a solution is injected underground to dissolve uranium from surrounding rock and sand before being pumped back up for extraction—common practice in Kazakhstan.

Second, mined and milled uranium is converted into uranium hexafluoride gas, a crucial input for the enrichment process.

Third, uranium is enriched to increase its fissile U-235 content—from 0.7% to 3-5% for LEU fuel used in current reactors and 5-20% for HALEU fuel used in next-generation reactors.

After enrichment, uranium is processed into pellets, which are then used to manufacture fuel rods.

Who Controls the World’s Uranium Supply?

Half of the world’s identified uranium reserves are concentrated in just three countries: Australia (28%), Kazakhstan (13%), and Canada (10%). Russia holds approximately 8%.

Canada was once the world’s largest uranium producer, but since 2010, with the rise of in situ leach mining, Kazakhstan has overtaken it.

In 2022, Kazakhstan—a former Soviet state and close Russian ally—accounted for over 40% of global uranium production. Russia produced 5%.

In 2023, the U.S. produced less than 0.5% of the global uranium supply—just 23 tonnes. A far cry from its Cold War peak. The U.S. has uranium-rich deposits in the Colorado Plateau, and in the 1980s, it produced over 15,000 tonnes annually. In 2022, nearly half of the uranium used in U.S. reactors came from Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan.

Change is slowly underway. In 2024, the U.S. saw the first new uranium mines open in nearly a decade.

Who Holds the Power in Uranium Enrichment?

After uranium is mined and extracted from ore, the next critical steps—conversion and enrichment—are far more complex. Many nations have attempted to master this process, but only a few have succeeded.

Currently, Russia and China control just under half of global conversion capacity and together produced over half of the world’s uranium hexafluoride in 2022. The U.S. holds around 10% of conversion capacity, while its allies France and Canada account for the rest.

In the U.S., enrichment capabilities were first developed during the Manhattan Project to produce atomic bomb cores. During the Cold War, the U.S. expanded enrichment primarily to support its nuclear weapons program and counter the Soviet threat. However, the U.S. relied on a more energy-intensive and costly method—gaseous diffusion—while the Soviets developed a cheaper alternative using centrifuge technology. After the Cold War, the U.S. relied on cheap, downblended uranium from Soviet-era warheads under the Megatons to Megawatts program, while Russia’s more cost-effective centrifuge technology further undercut U.S. enrichment facilities, leading to their slow decline.

Russia controls 40-50% of global enrichment capacity, and together with China, they account for around 60%. China is rapidly expanding its capacity to support its fast-growing nuclear fleet.

Russia supplies one-quarter of the enriched uranium used by U.S. nuclear reactors. In the U.S., enrichment has so far been limited to a single facility in New Mexico, owned by Urenco—a company jointly held by the British and Dutch governments and two German utilities. Now, new facilities are beginning to emerge. Centrus, a U.S.-owned company, is making strides in enriching HALEU fuel in Ohio. Orano, owned by the French government, is heavily investing in enrichment capacity at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Cameco, a publicly traded Canadian company and the world’s second-largest uranium producer, is working with Silex Systems of Australia on laser enrichment—a breakthrough technology that could give Western nations a strategic edge.

How Fukushima Stalled the West’s Nuclear Revival

Before the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011, a second nuclear renaissance was taking shape. After two decades of stagnation since the 1980s—driven by rising nuclear plant costs and slowing electricity demand—there was renewed enthusiasm. By the early 2000s, new investments were flowing into next-generation reactors, and nuclear energy’s low-carbon credentials aligned nicely with the global efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

But after Fukushima, the momentum collapsed. Japan and Western nations abruptly halted funding for new nuclear projects and withdrew investment from the supply chain that sustained the industry. It was as if a wrench had been thrown into the machinery. Meanwhile, Russia and China pressed ahead, expanding their nuclear programs and domestic supply chains while the West scaled back its reliance on nuclear energy. Westinghouse Electric, once a cornerstone of the industry, was forced into bankruptcy.

Despite today’s renewed enthusiasm for nuclear power, past setbacks have left many surviving companies risk-averse, hesitant to take the bold action needed to rapidly scale up fuel and reactor supply chains independent of Russia and China. Russia and China continue to dominate the nuclear energy landscape, with China likely a decade ahead of the U.S. in deploying next-generation reactors at scale. As a result, the U.S. and much of the world remain increasingly dependent on Russia and China for nuclear fuel.

The U.S. Push to End Russian Nuclear Dependence

As a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and recognizing Russia’s grip on the uranium fuel trade and its implications for energy security, the U.S. in 2024 passed a bill to ban Russian-produced uranium fuel. But given the heavy dependence on Russian imports, an immediate ban would have been suicidal. With U.S. nuclear reactors holding about three years’ worth of fuel supplies, waivers were granted until 2028 to allow continued imports from Russia.

The goal of the ban is to force U.S. utilities to sign contracts for domestically produced nuclear fuel. By creating demand certainty, the policy aims to encourage companies to invest in domestic supply.

This protectionist shift in nuclear energy mirrors trends in other strategic industries, such as rare earth minerals, where the U.S. remains heavily dependent on China. It reflects a broader disentangling from the one-way trade links formed during globalization, shifting instead toward a diversified network that favors U.S. allies.

Several forces have fueled this protectionist push in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of global supply chains, proving that reliance on a single country is a dangerous gamble. China’s dominance in green technologies and its control over critical mineral supply chains—essential for semiconductors, electric motors, solar panels, and batteries—has become a national security concern. China’s expanding influence in strategic regions—from the South China Sea to the Panama Canal, Malacca Strait, Africa, and South America—has made it a geopolitical rival to the U.S.

In nuclear energy, the wake-up call was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which forced nations to reconsider their energy security. Even at the height of the Cold War, natural gas shipments from the Soviet Union to Europe never faced the same disruptions and restrictions triggered by Russia’s 2022 invasion.