Long-term isolation of nuclear waste - is there a solution?

intergenerational fairness | step-wise approach.

This reading is part of a series: Nuclear Waste Disposal

Nuclear waste poses multiple problems - from its risk to our health to its possible use in developing weapons. Because of these problems, a convincing solution to nuclear waste storage is thought by many to be a prerequisite to expanding the use of nuclear energy.

Nuclear energy has been the single largest source of carbon-free energy in the US for several decades. It would have been an even more significant contributor to our energy today if we had not abandoned its development after the 1980s.

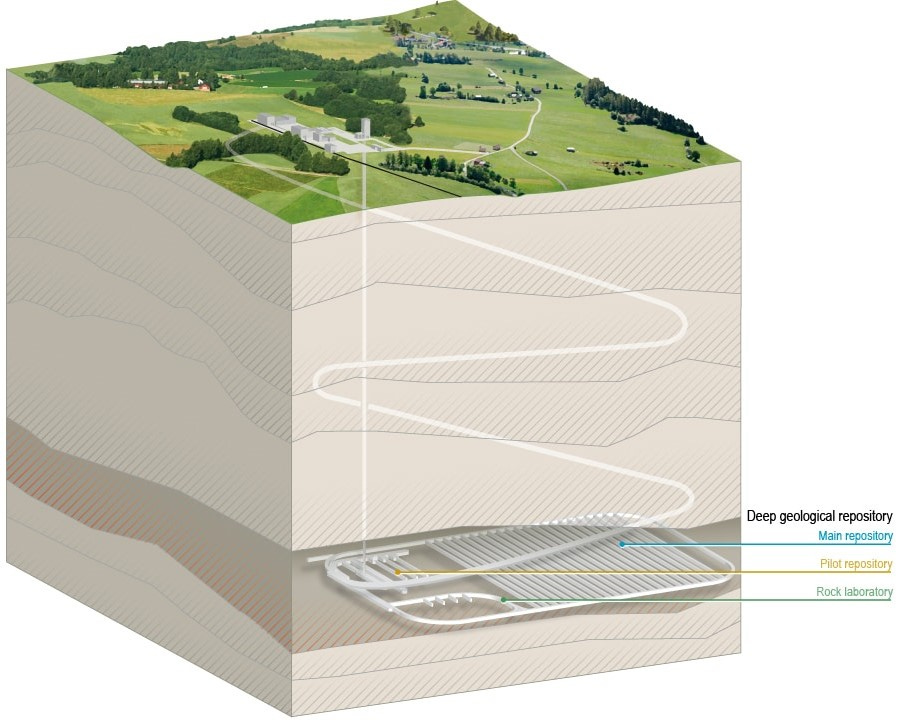

No matter how clean the energy that the nuclear option offers, the problems posed by nuclear waste cannot be dusted under the rug. These real and complex problems are not purely technical and involve components of social science and ethics. However, even the technical discussion has several options to consider, like long-term surface storage and geological disposal.

Further discussion about the technical obstacles can be found here: (link)

Even if no technical obstacles existed to constructing a functional geological disposal facility, choosing a geological repository over surface storage is about intergenerational fairness and not imposing the cost of surveillance and management on future generations. The argument goes - if we gain the benefits of nuclear energy, we must also bear its costs. This idea extends over to other sources of energy, too, e.g. for more than two centuries, previous generations have used coal to improve their living standards by employing cheap energy. The cost of this, the carbon dioxide they have released, was not internalized but passed on to us, and the resulting global warming and climate change is now our burden to bear.

But fairness also extends to providing future generations the choice to do what they feel is best for them. This means if we build a repository today and seal it, we take that choice away from them. Future generations may judge the spent fuel as valuable and want to use it. Or they may find a better option to dispose of the waste. Should we take that choice away from them?

These questions are complex societal questions that may sound simple but are burdened by the heavy weight of responsibility.

Given the challenges that developing a geological repository has posed, there is growing support for having a repository that is developed in steps, allows easy retrieval if needed and keeps the doors open for a longer time, with the ultimate aim of permanent closure [1].

This would allow monitoring of the performance and efficacy of the engineered barriers and for improvements to be made from observation and experience. This would also allow retrieval if a future generation wants to use the uranium and plutonium in the spent fuel for electricity generation.

This way, we could deliberately and cautiously move towards a permanent disposal option and thus still honour our responsibility while keeping the option open for better technology to prove its efficacy. It is a compromise between doing nothing and doing so much as to take the option of reversibility away from future generations.

References:

[1] National Research Council, Disposition of High-Level Waste and Spent Nuclear Fuel: The Continuing Societal and Technical Challenges. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2001. doi: 10.17226/10119.