The Geography Problem of Green Steel

Why Hydrogen Demand for Steel May Be Regional, Not Global

The hydrogen economy story rests on a powerful idea: that demand will emerge broadly across the industrial landscape — especially in hard-to-abate sectors like steel, shipping, and chemicals. Many projections treat hydrogen like a future commodity that will scale everywhere, from Europe to Japan to Australia, with global infrastructure rising to meet global need.

But what if that assumption is wrong?

Steelmaking is supposed to be one of hydrogen’s anchor markets. It’s the poster child for hydrogen demand in most long-term models. But hydrogen-based steelmaking may not happen where the steel industry operates today. It may happen where power is cheap, not where steel is consumed.

The shift from coal-based blast furnaces to hydrogen-based DRI doesn’t just change the fuel — it changes the economics of place. Hydrogen production depends on access to low-cost, renewable electricity. Without it, hydrogen-based steel is simply too expensive to compete.

If hydrogen-based steel production concentrates in a few regions — renewable-rich hubs like Australia, Brazil, the Middle East, or North Africa — the hydrogen economy won’t scale evenly across the map. It will scale where the inputs make sense.

This isn’t just a problem for hydrogen producers and infrastructure investors. It’s a decision steelmakers themselves are facing right now: Do they spend billions retrofitting aging blast furnaces in high-cost power regions like Europe — or do they shift new green production to where the energy is cheap and green from the start?

How that choice plays out could reshape not just hydrogen demand, but the entire geography of global steel.

Why Energy Cost Shapes Steel Geography

The logic of steelmaking has always followed the logic of its energy inputs. In the age of coal-based blast furnaces, steel production naturally clustered near coal mines. Energy was bulky, expensive to transport, and central to the economics of the process.

Hydrogen-based steelmaking reshuffles that map. In this model, coal is replaced by hydrogen — and hydrogen itself is simply a carrier for energy, produced through electrolysis powered by electricity. This puts the cost of electricity, not coal, at the center of the equation.

But not all electrons are created equal.

Electricity costs vary widely between regions. Renewable power in sun-rich or wind-abundant areas like Australia, Brazil, the Middle East, or North Africa can come in at a fraction of the price seen in Europe, Japan, or South Korea. This cost gap matters. Producing green hydrogen via electrolysis is inherently electricity-intensive — so even small differences in power prices cascade into large differences in hydrogen cost.

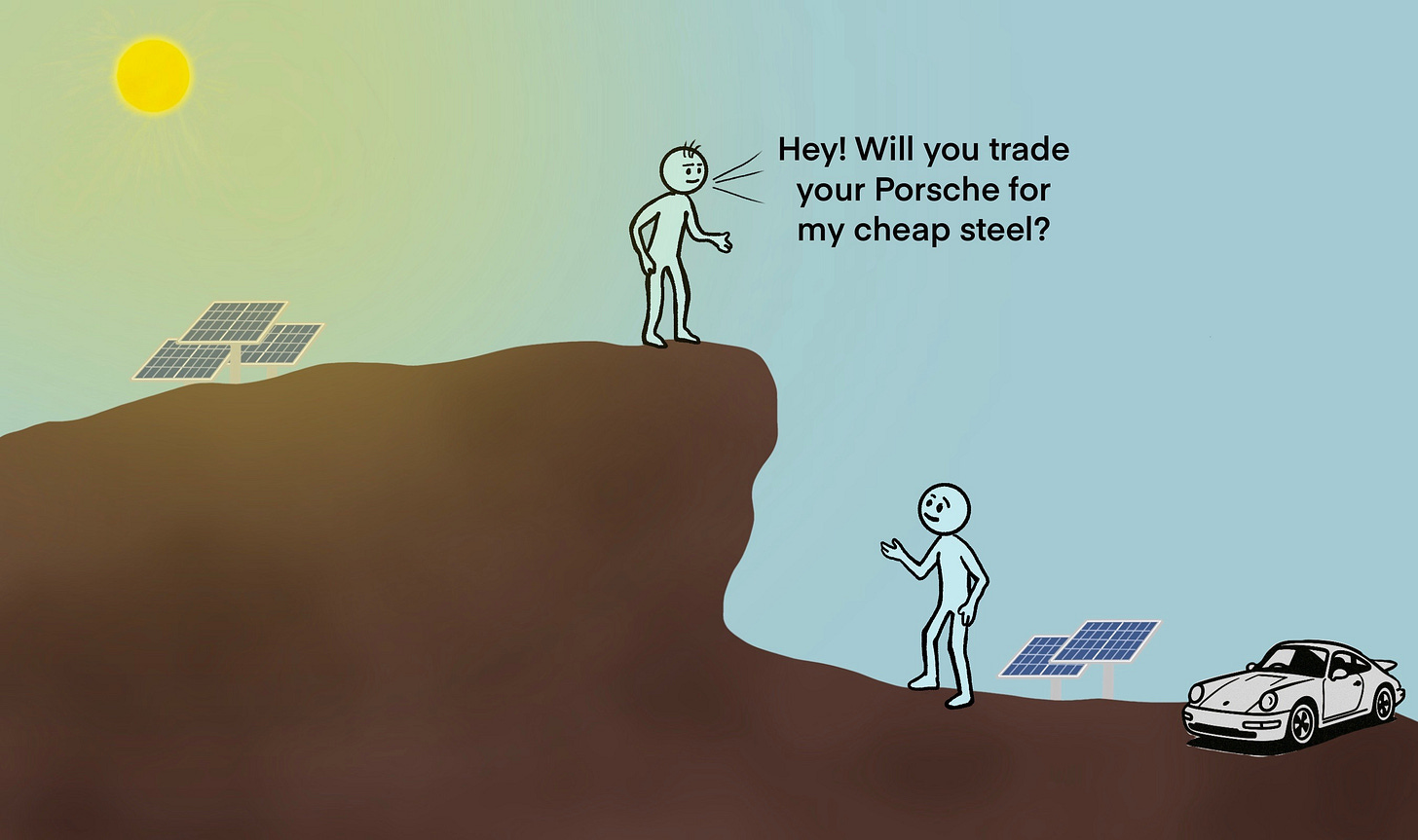

This shift forces a critical question for steelmakers: If the cheapest hydrogen is available far from home, does it still make sense to retrofit legacy blast furnaces — or is it better to build new capacity where the fuel is cheapest?

The energy input no longer dictates just the emissions profile. It may dictate the geography of production itself.

The Local Hydrogen Risk for High-Cost Regions

Europe, Japan, and Korea are among the world’s largest producers of steel. But they are also among the regions facing the highest electricity costs — and with that, some of the highest green hydrogen production costs.

This creates a fundamental tension. These regions have strong policy commitments to decarbonization, but they may simply not be the cheapest places to make green hydrogen at scale.

That raises a tough strategic question for steelmakers and hydrogen producers alike: Will these regions invest heavily in local hydrogen production and green steelmaking — or will they choose to import semi-finished steel from regions where the economics work better?

If the answer is import, global hydrogen demand doesn’t vanish — but it doesn’t localize. Hydrogen use stays at the export hubs, not at the consumption centers.

This outcome would dramatically reshape hydrogen infrastructure plans. Local hydrogen production, pipelines, and electrolyzer projects in high-cost regions may struggle to find viable offtake if the steelmakers they expect to supply opt instead to source low-carbon sponge iron from abroad.

The risk isn’t just technological or cost-based. It’s a geography mismatch between where hydrogen would be produced and where demand was originally forecast to appear.

Industrial Strategy vs. Pure Economics

On paper, the cost advantage of producing hydrogen-rich steel in renewable-abundant regions looks overwhelming. But steel is not just any commodity. It is foundational to national security, defense industries, and economic sovereignty. And that makes the story more complicated.

Governments may not be willing to let market logic alone decide where steel is made.

The European Union is already moving in this direction. Tools like the Emissions Trading System (ETS) and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are designed not only to cut emissions but to prevent carbon leakage — where dirty imports undercut domestic producers. Japan and Korea, both major steel consumers, are also debating industrial policies to protect strategic manufacturing sectors.

This raises a critical uncertainty for investors: How far can policy bend the cost curve? And for how long?

Subsidies, tax credits, and protective tariffs can support local hydrogen-based steel production even where renewable power is expensive. But if those supports weaken — or if green steel made abroad becomes dramatically cheaper — local hydrogen demand could collapse.

There’s no guarantee that governments will keep policy levers in place indefinitely. Industrial strategy may hold the line in the short term. But economics have a way of reasserting themselves over time.

For hydrogen producers and infrastructure developers, this isn’t just background noise. It’s the political variable that could decide whether a billion-dollar electrolyzer project finds customers — or sits idle.

What This Means

Hydrogen is often pitched as a globally scalable solution — a flexible decarbonization lever that can fit into energy systems anywhere. But steelmaking exposes a harder truth: hydrogen’s economics are deeply local.

The viability of hydrogen-based steel depends on power prices first, not hydrogen prices. And because renewable electricity costs are geographically uneven, hydrogen demand will be too.

This means hydrogen producers and infrastructure investors can’t rely on the idea that steel demand will translate directly into hydrogen demand wherever they happen to operate. They need to ask a harder question: Will hydrogen demand show up where I’m producing — or will it concentrate somewhere else entirely?

If hydrogen-based steelmaking consolidates in a handful of renewable-rich regions, the size of the hydrogen market in Europe, Japan, and other high-cost areas could be smaller than most forecasts suggest. Local electrolyzer projects, pipelines, and hydrogen infrastructure may struggle to justify their economics if the steelmakers they were meant to supply opt instead to source low-carbon sponge iron or finished steel instead.

This doesn’t mean hydrogen demand vanishes. But it does mean that hydrogen demand may be hub-and-spoke, not grid-like. It may emerge as tightly clustered production zones feeding global supply chains, rather than broad-based regional networks.

For investors, that reshapes the thesis. Hydrogen won’t automatically scale everywhere. The opportunity lies in picking the right geography — not just the right technology.

The hydrogen economy has always been sold as a technological breakthrough for hard to abate sectors — a clean molecule with the flexibility to decarbonize almost anything. But steelmaking shows that the real economic challenge isn’t just the chemistry. It’s the geography.

Hydrogen-based steel doesn’t just need electrolyzers and renewables. It needs the right renewables in the right places at the right price. Without that, the model struggles to compete.

For investors and infrastructure builders, this is more than a footnote. It’s a fundamental design constraint. The success of hydrogen in steel — and perhaps in heavy industry more broadly — may depend not on how good the technology gets, but on where you place your bets.

Hydrogen isn’t automatically global. It may never be.

And for hydrogen producers and their backers, understanding this early — before the capital is committed — may be the difference between riding the first real industrial wave of the hydrogen economy… or standing on the wrong side of a shifting map.