Nuclear competition | Grid resilience | AI ambition | EV's future

I am looking at these 4 things in energy this week.

I am looking at these 4 things in energy this week:

The purchase of South Korean company KHNP’s nuclear reactors by the Czech government has been halted by the EU, pending further investigation. Competition in nuclear energy is just beginning to heat up. But is it also starting to get dirty?

The cause of the recent country-wide blackout across Spain is still to be revealed. What might the implications be once the truth emerges?

President Trump’s recent trip to the Middle East highlighted the region’s ambition to take a stake in AI’s future.

Honda has scaled back its EV ambitions amid slowing demand. What does that signal for the future of electric vehicles?

The purchase of South Korean company KHNP’s nuclear reactors by the Czech government has been halted by the EU, pending further investigation. The decision came after French rival EDF alleged that KHNP had received unfair state support from the South Korean government—support that allowed it to underbid EDF for the Czech nuclear power project. The EU’s newly introduced Foreign Subsidies Regulation—invoked in this case—is designed to protect European companies from foreign competitors that benefit from distortive state aid.

Several EU nations are actively exploring the expansion of their nuclear energy capacity. Demand for nuclear power within the Union is poised to rise. Even Germany, long a staunch opponent, has shifted its stance recently—agreeing to categorize nuclear power on par with renewable energy. For European reactor and fuel manufacturers, this could represent a golden moment, a rare alignment of policy, demand, and public will.

But lower-cost foreign alternatives are increasingly viewed as a threat to domestic industrial capabilities. The precedent is clear: consider how China, through aggressive state-backed investments, came to dominate green technologies, rendering EU firms uncompetitive and dependent. Northvolt is merely the latest chapter in that unfolding story.

For the Czech buyer—the national utility—this intervention likely feels unjust. Any prudent buyer would naturally prefer the most cost-effective option. Nuclear plants, after all, are enormously capital-intensive undertakings, even under ideal conditions—which rarely materialize at this scale. EDF’s flagship project, Hinkley Point C in the UK, has suffered from delays and ballooning costs. By contrast, the Barakah Nuclear Power Plant, constructed by KHNP in the UAE, demonstrated a more successful track record, particularly in timely delivery. So the question arises: is EDF genuinely concerned about fairness—or simply trying to protect its neighborhood markets and future demand pipeline?

For Czech ratepayers, an EDF win could translate into higher electricity prices. The broader question is this: What should the EU prioritize? Opting for the lowest bid may entail awarding the contract to a foreign—possibly state-supported—firm. The direct benefit would accrue to EU consumers. In that light, one might see this as South Korea subsidizing Czech electricity bills. But that is a short-term view.

And therein lies the dilemma. Does a short-term economic gain come at the cost of long-term resilience? If EU-based companies lose market share and capacity, energy security risks grow. Again, the example of green tech looms large—one nation and its firms now command an outsized share of global production. That grip was forged not by innovation alone but by aggressive, subsidized expansion, which undercut foreign competition on both price and scale.

Yet even if KHNP did receive unfair state support, is there no advantage in allowing it to build reactors within Europe? Such projects unfold over decades and would likely deepen EU-South Korea strategic ties. State support does not inherently disqualify a company’s technical competence. Even without state support, KHNP may be cheaper and more effective. EDF, by contrast, may be trailing where it matters most.

Rather than issuing outright bans, the EU could consider a calibrated approach: impose targeted financial offsets to level the playing field. This would preserve competition while giving domestic players a real incentive to improve. Protection should not mean isolation. It should mean preparation—so that when the competition arrives, we are not merely shielding weakness, but cultivating strength.

The cause of the recent country-wide blackout across Spain is still to be revealed. What might the implications be once the truth emerges? Some have pointed fingers at the nation’s heavy reliance on renewable energy. Others suggest it may have been a deliberate act—an orchestrated cyber attack. Government officials remain skeptical of both claims, yet concede that a cyber intrusion, however unlikely, cannot be fully ruled out. Ongoing investigations are expected to shed more light.

Spain, owing to its geographic advantage, is rich in solar and wind resources, and has invested heavily in both. Today, nearly 70% of its power grid is supplied by renewables. This makes Spain one of the foremost examples of large-scale renewable integration in Europe. And so, when a nationwide blackout occurs, suspicion naturally falls on the resilience of a system so dependent on intermittent sources.

The question isn’t merely what caused the failure—but whether the grid’s architecture is robust enough to handle the volatility that comes with green energy at scale.

Why is it crucial that the investigation be thorough? It is well understood that increasing renewable penetration places additional stress on transmission infrastructure. Critics argue that Spain’s grid has not sufficiently adapted to the changing dynamics of decentralized, weather-dependent generation. If this blackout stemmed from technical shortcomings rather than malice, then identifying the exact fault line becomes vital—not to assign blame, but to extract lessons. Other countries, many of which are following the same renewable-heavy trajectory, depend on this knowledge to avoid similar vulnerabilities. Spain, in this context, becomes a case study.

But if the cause was cyber sabotage—then who stands behind it? Russia, as always, looms in the background. Spain’s geographic distance from Eastern Europe has long shaped its strategic posture. Unlike Poland or the Baltic states, Spain has not felt the shadow of Russia with the same immediacy. Consequently, defence spending has remained low—among the lowest in NATO—while domestic priorities have taken precedence. In Eastern Europe, public opinion more readily embraces military expenditure; the threat feels near, visceral, unforgotten.

If this was a cyber attack, and if it bore the fingerprints of Moscow, what would that mean?

Geography, once a shield, may no longer offer safety. The invisible front lines of cyber warfare bypass borders, oceans, mountain ranges. What does that realization do to a country’s psyche? To its politics? Does it lead to a reassessment of national security? A rise in defence budgets? Or does the moment pass—filed away as an isolated event, half-remembered by the next season?

President Trump’s recent trip to the Middle East highlighted the region’s ambition to take a stake in AI’s future. Projects like Humain, an AI hub launched by Saudi Arabia, are a step in this direction.

Why does the Middle East want this so badly? The region’s rise over the last five decades has been driven almost entirely by fossil fuels. But in a world increasingly moving away from them, any petronation that fails to reposition itself—fails to diversify its economy—risks years of stagnation and declining wealth. AI is seen as a critical opportunity to shift away from traditional strengths and build a more resilient economic foundation.

What are the Middle East’s advantages? The ability to deliver massive projects quickly has long defined cities like Dubai and Doha. Saudi Arabia’s Neom city—despite recent funding challenges—still stands out for its ambition, unmatched in scale by anything comparable in the West. The region’s autocratic systems provide the centralized authority often needed to push through large infrastructure projects fast. It also has abundant energy—not just oil and gas, but also solar and wind. And NIMBY is not a phrase many Saudis are familiar with. Then there’s capital. Sovereign wealth funds, built on decades of oil revenue, offer a deep pool of investment that AI companies will be eager to access.

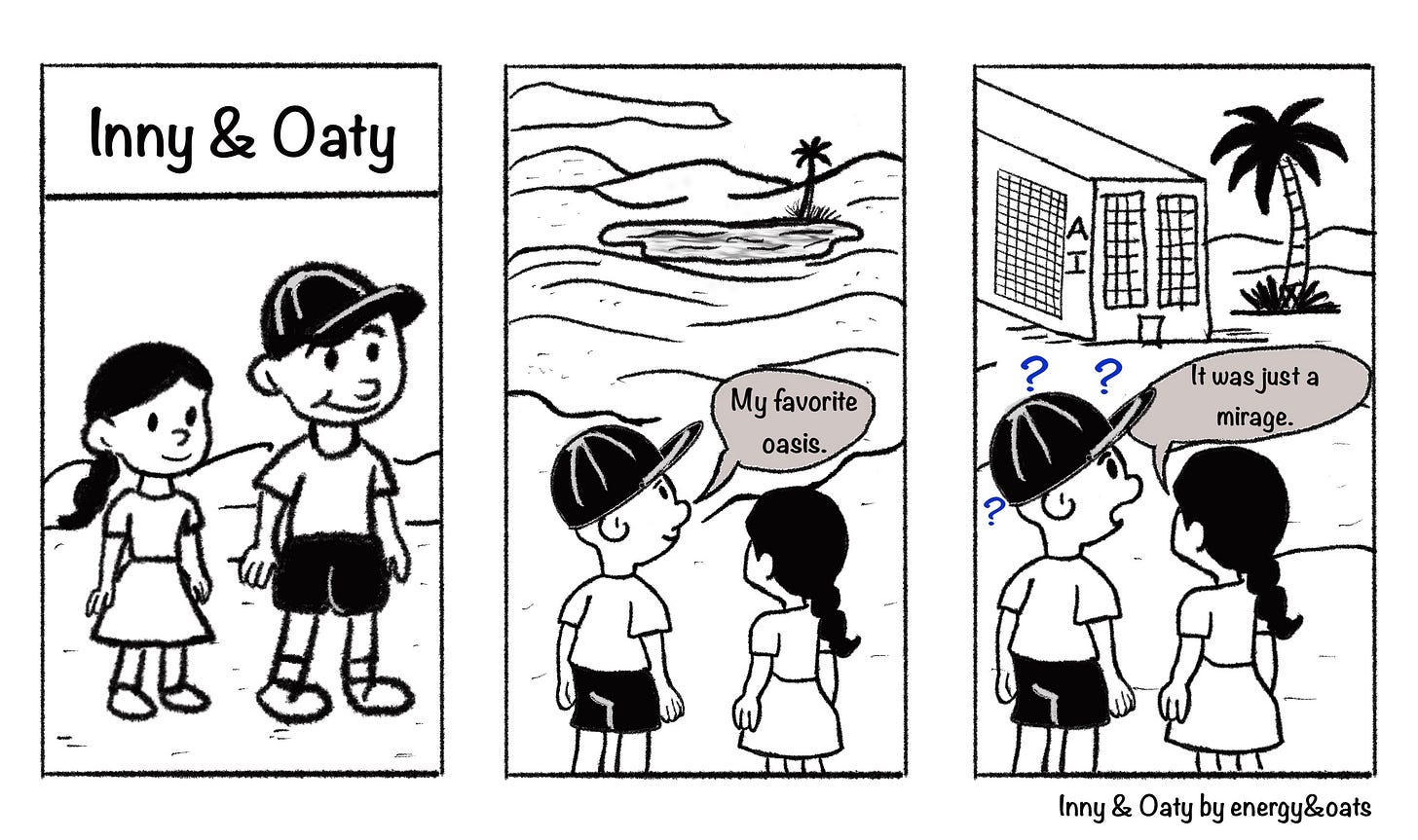

The Middle East wants to position itself as a place where AI companies can build data centers quickly, tap into cheap energy, and get to business without distractions. At its core, this is a bet on AI infrastructure.

But the Middle East isn’t alone in its ambition for AI.

The red carpet they rolled out for Trump was a strategic effort—to make the region acceptable for U.S. AI expansion at a time when global dealmaking has become far more difficult. Under Trump’s protectionist stance and tariff threats, such expansion could only have happened with his direct involvement. This was understood clearly by the region. And they acted on it, quietly but effectively.

Honda has scaled back its EV ambitions amid slowing demand. What does that signal for the future of electric vehicles? The company had previously set a goal of making 30% of its car sales electric by 2030, but that target has now been abandoned. Instead, Honda will focus on expanding its hybrid lineup in the near term.

This mirrors a broader trend across the auto industry over the past year. Automakers are seeing a cooling of demand in their EV segments, while hybrid sales continue to grow strongly. The industry also remains highly vulnerable to the trade disruptions triggered by President Trump’s policies. In this climate of uncertainty, companies are leaning toward caution. For many, even without the shocks brought on by tariffs, the energy transition and the rise of Chinese EV manufacturers represent a once-in-a-generation disruption. Faced with that scale of change, automakers are choosing to be conservative with their investments.

The main culprit behind the slowdown in EV sales is that most electric vehicles still target the premium segment. Broader adoption will require customers to feel more confident about range and charging access. Range anxiety remains a stubborn barrier. While many current EV owners enjoy the convenience of a driveway and a private charging port, that’s a luxury not available to all car buyers.

Still, the current slowdown in EV growth shouldn’t be mistaken for a long-term decline. Battery technology continues to improve—costs are falling, performance is rising. As charging infrastructure expands and range anxiety recedes, EVs are likely to regain momentum and grow their market share.

This should be seen as a short-term reorientation. After the post-COVID enthusiasm and investment surge, a period of adjustment was not only inevitable—it should have been expected.