The rise of AI atop the ash heap of sustainability

There is now a sustained push to revive fossil fuel energy sources to power AI

There has been a transition from an environment-focused narrative 3–4 years ago to what has been, in recent months, a complete reversal. There is now a sustained push to revive fossil fuel energy sources, especially in the US. Several forces have come together at the same time to bring this about, but I think there are three most visible ones that highlight the nature of the change and also perhaps bring a better understanding of why environmental focus was first embraced and why it has so quickly been abandoned.

Interest rates

Low interest rates seem as vanilla a factor as one can pick out from the assortment, and yet they’ve been, in many ways, a powerful driver. The world of finance works on profits and returns above any other incentive, even if sometimes the marketing of an investment may point toward altruism as the overriding factor.

In the rock-bottom interest rate environment from 2020–2022, and with an expectation of lower long-term rates, capital-intensive energy projects—renewables fall in this category—became attractive. The low interest rate also made funding these projects cheap and more attractive than lower capital intensity fossil fuel projects. There was another advantage of funding these projects—they helped investment firms market themselves as climate warriors who were leading the charge toward solving the climate change problem.

Marketing teams nicely wrapped up the action into something that investors could gobble up, that offered something other than just a potential for good return. Sustainability became a way to differentiate against other forms of investments.

But it was not expected at this time that inflation would emerge so quickly after the economic shock of 2020 and that the Fed would be set on a path of increasing interest rates. Higher rates emerging after 2022 deflated the interest in sustainability as capital-intensive projects became financially unattractive. A few other events also happened simultaneously that put fuel on the fire.

Ukraine

The war in Ukraine started in early 2022 and severely impacted gas supplies to the EU. This new environment meant that LNG projects would now not only benefit from their lower capital intensity vs. renewable projects in a rising interest rate environment, but would also benefit from better profitability because of higher natural gas prices.

Energy security now became a front-and-center concern. And the US had plenty of gas to offer, but not many ways to carry it across the ocean. Its LNG projects had seen severe restrictions from the Biden administration. Why curtail such a national treasure, the narrative went. It was also well understood that for critical minerals used in green technologies, the US was heavily dependent on China. And Russia’s actions had shown how energy security was so important for national security too. Thus, energy security, like in Europe, also gained prominence in the US.

But another force was also impacting the way we were thinking about energy.

Big Tech's changing priority

The growth in AI has now become the central priority for the big money investors who, in the past few years, had stated sustainable development as their central priority. And whether you call them FAANG, Big Tech, or Hyperscalers, they represent the biggest pot of money flowing in and out of the fast-growing sectors that have most interested investors in the past decade. And AI is now their central priority, overriding anything else.

The long-term survivability of their business is now tied to their superiority in AI. Losing this race—no matter how sustainably you do things—means losing investors. Shareholders might forgive you for missing sustainability targets, but they would walk away if you lose the AI race. Sticking to sustainability goals at the expense of AI capabilities would generally be regarded as a poor business strategy today. A CEO pursuing such a strategy would certainly be at a high risk of losing their job.

And AI superiority is not necessarily superiority of software. The race is now in hardware. Who has the most AI chips at their disposal? Who has the biggest data centers? Who has the most energy capacity available to them—with little concern for how clean that source is—to train their large language models and to answer the new energy-intensive search queries?

The need for firm power

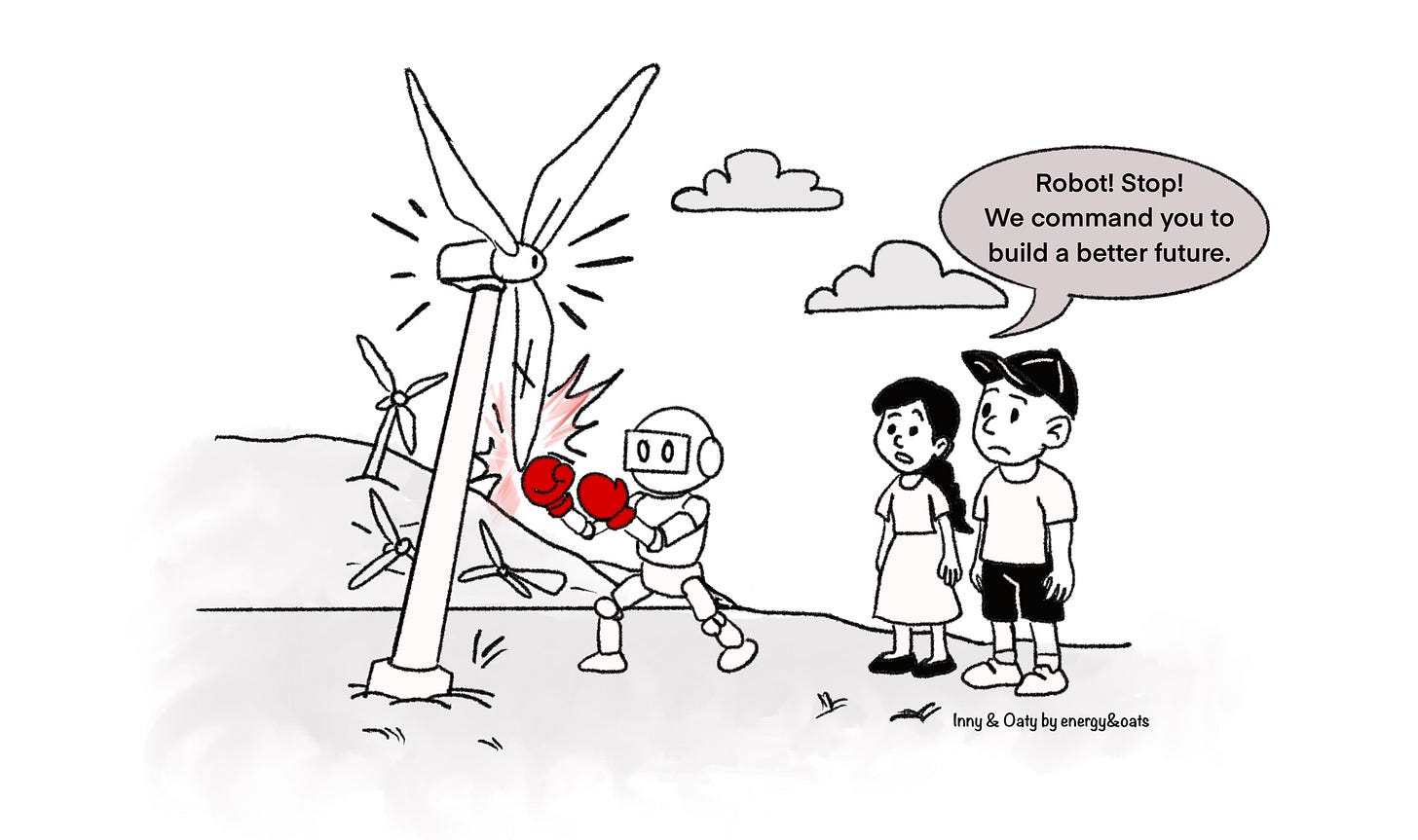

Rising power needs due to growing capabilities and use of AI have also highlighted the need for firm power—uninterrupted power. AI data centers prefer energy sources that can deliver power on demand so that the data centers themselves don’t have to slow down when the sun stops shining or the wind stops blowing.

Today, grid stability is a front-and-center concern. There is a lot more awareness that intermittent sources like wind and solar are not a good fit for the needs of AI, which depends more on dispatchable power. There is also a growing awareness that as the intermittent sources become a larger share in the energy mix, it would make the grid more unstable if there is not a counterbalancing source that is large and flexible enough to offset their intermittent nature.

Therefore, it is not surprising that nuclear has seen a revival over the past 3 years, especially among the AI leaders who see it as the ideal off-grid option that wouldn’t require either a connection to the grid or a pipeline—both of which have shown several barriers to growing quickly enough. However, nuclear is also seen as only a long-term alternative and not a short-term solution since most next-generation projects have yet to build even a first-of-a-kind unit. But given nuclear is only a long-term solution, and given the priority for achieving AI superiority among companies and countries, favor for building more firm power sources that use fossil fuels has grown strongly, and their carbon intensity is no longer seen as a barrier. This has so far been for natural gas only; however, in some circles, there are growing calls for reviving coal as an energy source too.

Efficiency is not the first priority here

Big Tech companies are already reporting that their carbon emissions have increased by around 30 to 50% in the past 5 years, blaming this on the growth in data center energy consumption. AI queries are 10 times more energy-intensive than Google search queries. And although it may be tempting to think that AI searches have the ability to hit the bullseye in giving us the information we want on the first try, while we might spend significantly more time and energy, e.g., 10 to 20 Google search queries, to eke out that same information from the web, which is a reasonable claim to make, we should not forget that AI tools like ChatGPT have opened up unthinkable new avenues—like image generation or video generation—and created new use cases that were not even available to us before. This makes it a powerful new energy consumer. And given the priority today is acquiring power in an environment where the grid is becoming increasingly strained and a bottleneck to growth, and that acquiring firm power—especially from sustainable sources—to run AI data centers is becoming more and more difficult, it is not surprising that where the overarching aim is to achieve superiority in AI capabilities, it would most likely only happen by standing on the heap of ashes of a sustainable future.

That is not to say that there is no way to be found to make these systems more efficient in their energy use and function in a way that is more grid-friendly and more complementary to a renewable-heavy grid. For example, the heat management—which is a very energy-intensive part of data center operation—can be done more efficiently by placing data centers in cooler climates. Another way would be to use thermal storage techniques—like chilled water tanks or ice storage—which could allow energy used for cooling to align with renewable power generation, thus helping data centers to rely less on fossil fuel-derived firm power and therefore more on intermittent and environmentally friendly sources.

But there needs to be an incentive for companies to pursue these alternatives and make AI systems more efficient. Shedding the burden that Big Tech had once decided to bear and switching to fossil fuels is a simple solution to their problem. Political opinion today is clearly standing in their favor. Energy companies are planning new natural gas power plants at the fastest pace in years, driven by this new thirst for power, and are also cementing a new reality—that fossil fuels are going to stay around for longer than we had previously thought. Most investments being made in these plants come with an expectation that the plants will continue to produce power for at least a few decades. And there is such a rush for the gas turbines powering data centers that manufacturing backlog today is up to 5 years. This was seen as a dying sector just a few years ago.

And given the grid has become such a bottleneck to their growth, and given that it will always be a lot more difficult to expand the grid than to build a data center that needs its power, we will see a lot more cases where data centers either build their own power generators—whether it’s nuclear SMRs or natural gas turbine-based generators—or co-locate where the electricity generation plant is, or where the energy extraction is occurring. And that could mean that states that are producing the most natural gas could be very attractive destinations for data center companies that don’t want to deal with grid connection. Several states are clearly excited about this.

Implications longer term

If the use of natural gas continues to grow over the coming years—remember that new projects will stay operational for a few decades—and if the voice for climate change and sustainability also doesn’t vanish but, and this is reasonable to assume, only subsides temporarily before coming back stronger later in the decade, then we will see a growing acceptance of carbon capture projects to realign the reality to the commitments from countries and companies for reaching net zero around 2050.

Despite new priorities emerging today, the climate is still changing, global warming is still happening. At some point, a majority in society will come to a realization that action—urgent action—is required, if not for themselves and their world, then for the world that their kids and grandkids will inhabit. And given the way a new vigor is pushing the development of fossil fuels today, it would be very reasonable to think that a bright and profitable future will soon emerge for carbon capture projects to try and undo the damage. And these projects, while having faced intense criticism in the past, will then become a necessity. And even the past critics of such projects will be calling for more of them.