Where has all the excitement for EVs gone?

EVs still have a way to go before they can compete with gasoline powered alternatives in the West.

There is no denying that the rate of growth in EV sales in the US has slowed down. But an all-electric future in cars is still the general expectation among automakers. The feeling is that we’ll reach there, but it will be a bit slower than what the enthusiasm of two years ago suggested.

Most automakers that had revealed ambitious plans between 2020 and 2022 have scaled down their ambitions. Whether it’s automakers in the US or in Europe, all have modified their goals to 2030 and 2035.

Situation in the West

Recent actions and the general attitude of the current administration in the US about green technologies have dampened expectations of strong growth in the EV sector there. Many car makers are reviving gasoline models or delaying new EV models. But this is not the only challenge that exists in the US facing EVs.

People are definitely sticking to gasoline cars despite the growth in EV adoption in recent years. Cost and range anxiety are still major hurdles in the West.

Even before recent policy uncertainty, automakers were already seeing several persistent issues with widespread adoption of EVs. Most EVs being sold in the West are still more expensive than their gasoline counterparts, although that gap is falling. And even in the EU, which has a more supportive policy environment for EVs, the gap still exists, though it is narrower. Only in China have EVs become price-competitive with gasoline alternatives, largely due to the intense competition and falling battery costs in that market.

Range anxiety is still a big concern, especially in the US. Many car owners don’t have access to chargers on their home property and have to rely on public chargers. Lower per-capita public fast-charging access in the US will remain a hindrance to widespread adoption.

It is not surprising, therefore, that most EV owners are luxury car buyers who are buying EVs as a second car and who have private driveways and access to home charging for their EVs. Breaking into the general consumer market is still a challenge. But note that this is a very Western phenomenon. In China, EVs are already cheaper than gasoline counterparts, and government subsidies are helping increase their adoption faster than ever. And public access to fast charging is much higher there than in the West. So the major barriers that still persist in the West have already been broken down in China.

After a rough 2024 for EU automakers from experiencing sluggish car sales and the existential crisis of competition from Chinese automakers, the EU has eased some of the requirements on domestic manufacturers to meet climate goals, like relaxation of its CO2 emissions standard so that manufacturers can avoid fines and meet the longer-term climate goal more gradually, in order to give them a breather to better compete with rising competition in the auto sector from China, especially in the EV space. The policy environment in the EU is friendlier to EVs than in the US and that should push adoption further in the coming years.

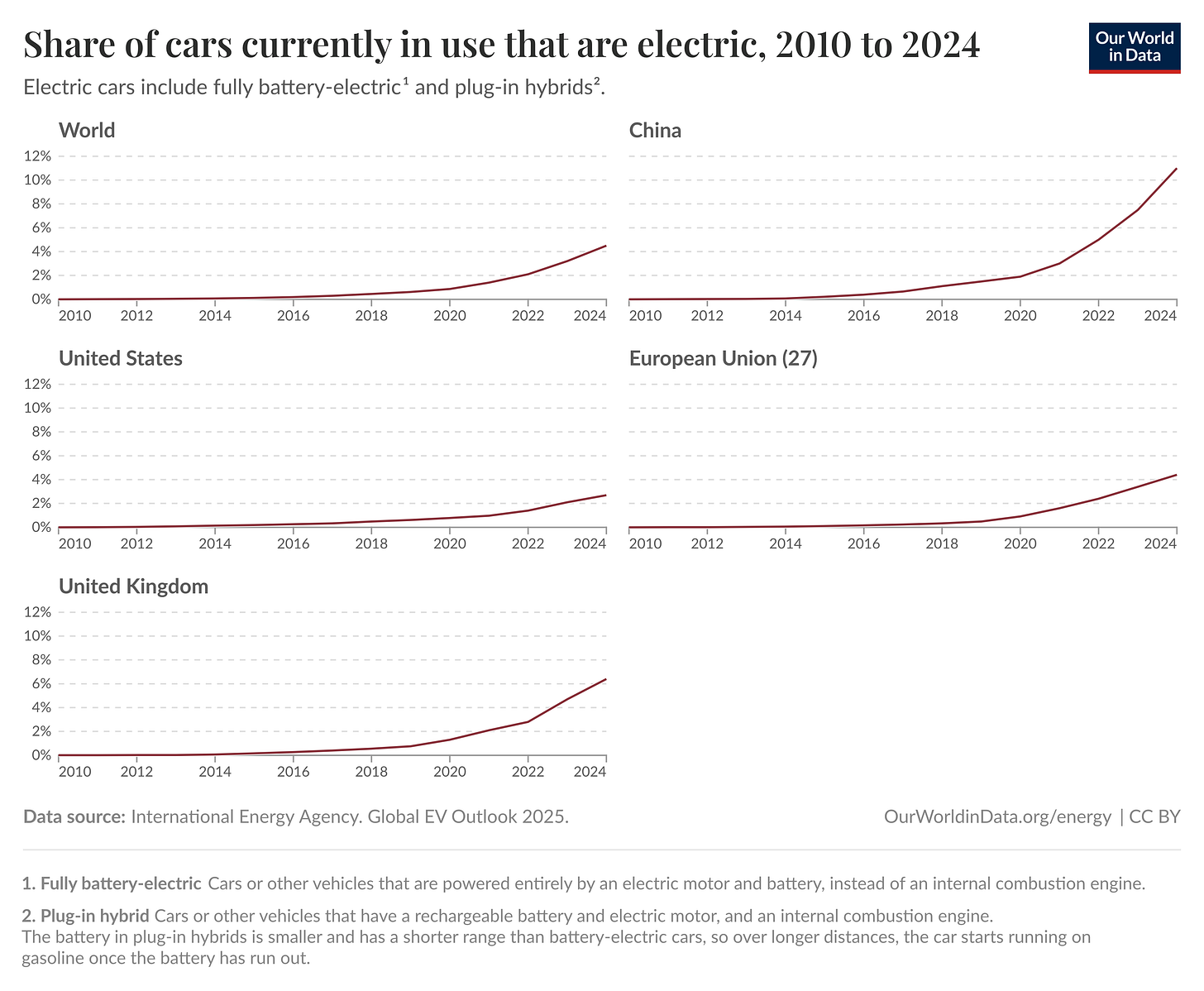

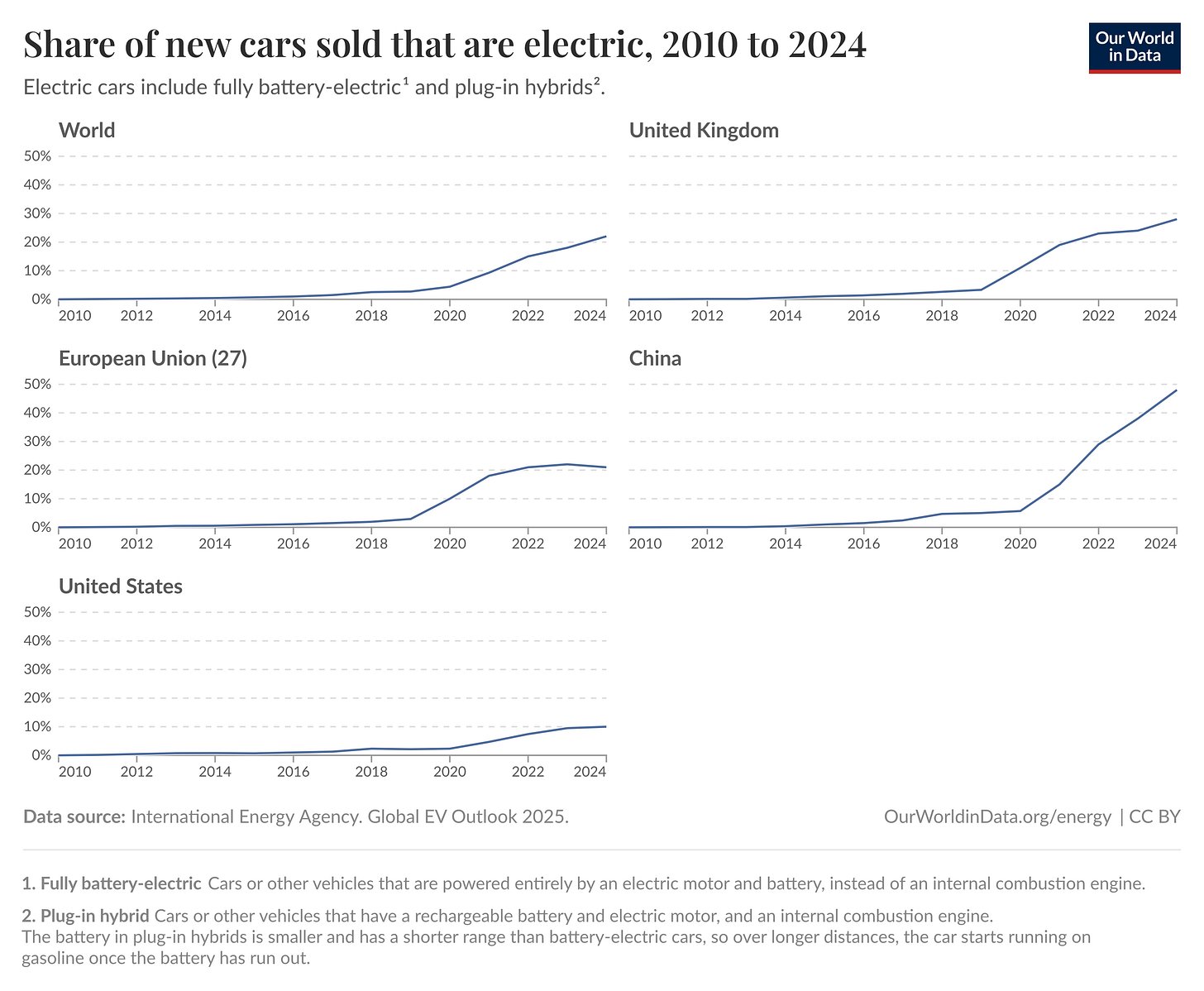

Despite these challenges, though, the growth trajectory of EVs remains strong globally, mostly due to China, and is continuously eating into the share of the new car market.

And although EV sales growth in the US was slower in 2024 vs. 2023, it was not negative. More EVs were sold in the US in 2024 vs. 2023. And let’s not forget that over the previous five years, the growth, although starting from a low base, has been quite explosive.

Situation in China

The progress of EVs in China is clear when you see that around 1 in 10 cars sold in the US are electric, while in China it is around 5 or 6 for every 10 cars sold in 2024.

In China, the government is actively trying to promote the adoption of EVs and replacement of older gasoline vehicles. There is obviously an energy security imperative to it, as well as an opportunity to break into the global automotive market that has traditionally been the territory of Western firms. If China is on one end of the support spectrum, pushing the country to adopt EVs, the US is on the opposite end of this spectrum today, actively trying to choke demand appetite. Europe is somewhere in the middle with some supportive schemes still there while others have not been renewed, to give domestic automakers more time to adapt.

The cost of EVs is another factor that is helping China move to an all-EV market sooner than other countries. In China, a large majority of the new EV models sold are cheaper than their gasoline counterparts, even without incentives. In Europe, they sell at a 20% premium, while in the US, the premium is even larger. The falling cost of EVs, especially in China, is generally due to falling prices of critical minerals and intense domestic competition among its battery and car manufacturers. But those cheaper EVs selling in China are unlikely to be sold in the West, where both the US and EU are aggressively trying to protect their domestic manufacturers from Chinese competition. But it cannot be denied that Chinese manufacturers have gained an upper hand in both the technology and the manufacturing capabilities and are able to produce EVs that are better, at lower cost, and at much higher volumes than can be said of the manufacturers in the US or EU. They do have a leg up.

Another reason for faster adoption in China is the rate of deployment of public charging stations. This has made EVs accessible to a larger public that doesn’t have the convenience of home charging. In the US, access to home charging is more widespread, which has also resulted in slower public charging buildout. But lower per-capita charger access, especially fast-charging access, is a major factor behind range anxiety that still affects consumers.

Situation of the Jugglers

In the US, the over-ambition of automakers towards EVs over the past few years is becoming clearer. The new technology has not been easy to master and the billions spent on it have only amounted to losses. And despite EVs still being sold as a luxury offering by these companies, many are losing money on each EV they sell. Ford, for example, has not seen the excitement it had expected when it first launched the concept for the F-150 Lightning, in the sales. Ford’s EV division has been losing money.

Both Ford and GM had expected demand for EVs to skyrocket and had, as a result, made investment decisions to increase capacity for producing EVs and their components such as batteries. But both Ford and GM have either slowed work on those plants or canceled projects and have delayed the launch of EV products. Some, like GM, have started to embrace internal combustion engines more enthusiastically and see a full transition to EVs as a multi-decade gradual transition rather than a 2030 or 2035 event, a stark contrast in tone from just two years ago.

The losses and the changing market environment have meant that car companies have started to lift the pedal off the accelerator on their EV ambition. Consumer enthusiasm has changed quite starkly too. This can be seen by a sudden increase in enthusiasm for hybrid models over EVs. And this is something that is being observed not only in the US but in the EU too and also surprisingly in China, where EV growth is so strong. This is to a large extent because many consumers are still not satisfied with the charging capabilities of their EVs. And although they want to switch, there is still that persistent issue of range anxiety. Alongside traditional hybrids, there has been rising interest in Extended Range EVs that have an onboard gasoline engine whose sole purpose is charging the battery. These have started to become a popular option for those really concerned about range anxiety among those that really want to switch to an EV. Car companies have responded by delaying their pure EV offerings in favor of hybrid offerings, and many are considering bringing in bridge offerings like the Extended Range EV.

In the EU, the picture among the automakers is similar, although they have the added stress of competition from China—which is not the case in the US. Western manufacturers had built a competitive moat in the internal combustion engine vehicle. The complexity built into the design and production made it difficult for new companies to emerge quickly and outcompete incumbents either on quality or on cost. EVs are a technology disruption. For many traditional car makers, it is an existential challenge. Car companies that had built an expertise in building superior hardware—the Porsches and Lamborghinis and Ferraris of the world—are having a tough time adjusting to an all-electric future. What would separate a 500km range VW Beetle from a 500km range Porsche if speed, range, and drive are all similar? What else are they offering their customers? This is the most important question that the car industry is currently grappling with. EVs level the playing field by making the drive—the mechanical bits—of one vehicle mostly indistinguishable from the competitor’s. This is a nightmare scenario for companies that had built hardware niches and an opportunity for new players that see competition taking place in other avenues like cost, customer experience, and luxury features.

Part of the reason for automakers being hesitant in making a switch to EVs is because the policy environment today is starkly different than it was in 2022. Back then, buyers were being offered incentives for purchasing EVs and being penalized for purchasing internal combustion engine cars. And that meant that the higher profitable gasoline vehicles for automakers suddenly became less attractive offerings, and the choice among many companies was either to try to become the next Tesla on the one end or risk being left behind by the transition on the other end. Most were pushing to have as many EV offerings as they possibly could. Offering attractive EV concepts also meant shareholders were rewarding you amply by almost instantly boosting the stock price. The policy environment and consumer preferences led to this. There was a degree of irrational exuberance in all of this.

Today the direction of policy has gone the other way. Support for EVs by governments has fallen in both the US, since President Trump came into power, and at the national level in the EU, led by Germany. Automakers have reacted by offering more models that are hybrids or gasoline-powered. The hope is to bring back profitability. The trade war initiated by the US has also not been kind to automakers, and they are, broadly speaking, taking a step back from all the enthusiasm for EVs that was seen in 2022.