Why Methanol Is Winning the Shipping Fuel Race — For Now

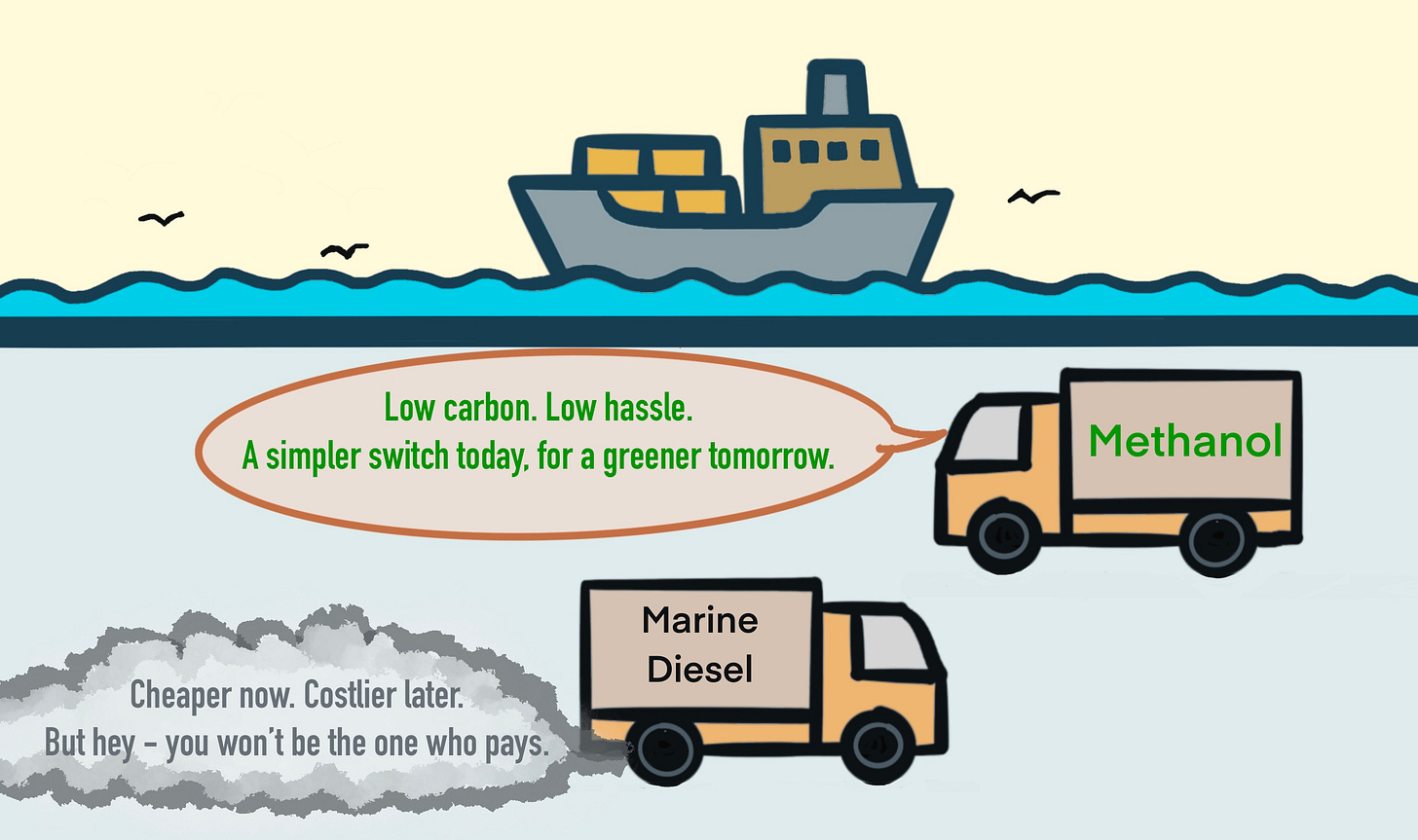

Methanol isn’t the endgame for clean shipping — it’s the fuel that works now, in a system built to resist change.

Deep-sea shipping — the massive container vessels that cross oceans — represents the beating heart of global trade. It also accounts for nearly 80% of the shipping sector’s greenhouse gas emissions. The industry as a whole emits about 3% of total global CO2, putting it on par with aviation.

That share is expected to grow. Shipping is hard to decarbonize. The vessels are long-lived, the distances they have to travel are vast, and the energy demands are high. The shipping industry is running out of time. With international pressure mounting and climate deadlines approaching, ship operators can’t afford to wait for the perfect fuel. They need something that works today — and increasingly, that something is methanol.

It’s not the cleanest option, or the cheapest. It’s not even guaranteed to be the long-term winner. But methanol is compatible with today’s infrastructure, can be handled with minimal upgrades, and fits with existing ship designs. That makes it uniquely usable.

This isn’t about choosing the best fuel. It’s about moving quickly.

A “Now” Fuel

Global shipping is a high-emission industry with an unusually long memory. A ship ordered today won’t enter service for 2–3 years. Once launched, it may sail for another 35-40. Vessels built today will still be operating in the 2050s. Every delay in fuel adoption ripples forward for decades. And most ports — especially outside Europe — aren’t yet ready for anything radically new.

In the European Union, the FuelEU Maritime regulation is forcing the issue. Vessels must begin reducing greenhouse gas intensity starting in 2025 — with escalating targets through 2050. Ships will face increasingly strict limits on greenhouse gas intensity, with penalties applied to vessels that fail to comply. The regulation doesn’t just reward progress — it punishes hesitation.

The challenge is that most alternative fuels aren’t deployable yet. Hydrogen is immature at scale. Ammonia raises serious handling and safety concerns. Infrastructure is either lacking or theoretical.

What the industry needs is a now fuel — something that works with current infrastructure, fits into existing safety regimes, and gives operators a way to comply without betting everything on the unknown.

Methanol isn’t perfect. But it’s doable. And in a sector driven by engineering conservatism and long-cycle investment, that counts for more than technical elegance.

Practical Fit

What makes methanol different is that it fits the system as it exists today. Unlike alternatives like hydrogen or ammonia, it’s a liquid at ambient temperature. That means it can be transported, stored, and bunkered using infrastructure that ports already understand. Retrofitting older ships to run on methanol is possible, and new dual-fuel engines are already in production.

From a safety and environmental standpoint, methanol is manageable. If spilled, it’s less toxic to marine ecosystems than today’s fossil-based marine fuels. It dissolves in water and biodegrades quickly. That matters in practice — especially in smaller ports or developing markets where leakage and informal bunkering practices remain common.

If you’ve ever seen bunkering operations along the Mekong Delta — small crafts pulling up to ferries with hoses and hand pumps, fuel dripping directly into the river — you know this isn’t theoretical. Leaks happen all the time. What matters is how forgiving the fuel is when it does.

That said, methanol is still toxic to humans — especially if ingested or with prolonged skin exposure. It’s not a harmless fuel. But compared to ammonia, it’s far easier to work with and far less dangerous in practical terms.

Ammonia, by contrast, is far more toxic, especially via inhalation. And being gaseous at room temperature, it requires entirely different handling protocols — not something every operator or port can adopt overnight.

Order Books

After LNG, methanol has become the most popular alternative fuel in the global order book, far ahead of ammonia or hydrogen.

Dual-fuel methanol engines — capable of running on conventional marine fuel and switching to methanol when available — offer flexibility during a transition period. That’s especially valuable in a regulatory environment that’s tightening faster than global fuel supply chains can adapt.

These ships aren’t short-term bets. They’ll be on the water for 35–40 years. And that gives methanol real gravitational pull — not just on engine designs, but on bunkering infrastructure, hydrogen sourcing strategies, and CO2 feedstock investments.

Ammonia might still win in the long run. But it’s methanol that’s shaping the market now. And when infrastructure gets built around a fuel — even a transitional one — it doesn’t disappear quietly.

The Cost Caveat

For all its practical advantages, methanol has a structural cost problem: it’s expensive to make cleanly. Producing e-methanol — the low-carbon version aligned with climate goals — requires two key inputs: green hydrogen and captured CO2. Both come with significant costs.

That CO2 input, in particular, is a bottleneck. Unlike ammonia, which uses nitrogen - the most abundant component of Earth’s atmosphere- pulled from air, methanol relies on carbon — and carbon is harder to find in clean form. Capturing CO2 from industrial sources can reduce emissions but still ties methanol to fossil infrastructure. Capturing it directly from the air is far more expensive. Some producers look to biogenic CO2 from biomass or waste — but that supply is limited and already in demand for SAF, biofuels, and synthetic chemicals.

This constraint creates a ceiling: even if methanol adoption accelerates, the fuel itself may not remain affordable — unless CO2 sourcing becomes cheaper, or synthetic production technologies improve rapidly.

That’s why methanol isn’t just fighting technical alternatives. It’s competing against other industries for the same feedstock. And that competition introduces volatility that shipping operators don’t control — but will eventually have to price in.

What This Means

Despite the cost hurdles, methanol still holds strategic value — precisely because of how shipping works. The industry doesn’t and can't decarbonize in sudden shifts. It moves through long arcs of infrastructure, regulation, and fleet cycles. And methanol, for all its imperfections, lets that arc begin now. Fuel that wins today is not going to be the one that's best in theory, but the one that can be slotted into these cycles with minimal disruption.

Methanol fits that pattern. It doesn’t require a wholesale rebuild of bunkering systems. It doesn’t force a fleet overhaul. It doesn’t demand entirely new safety protocols. For shipowners navigating uncertainty, those are not minor advantages — they’re decisive.

And that’s what gives methanol leverage. Not because it will dominate forever, but because it’s the fuel that enables movement while the rest of the system catches up. It gives ports a reason to act. It gives hydrogen producers a beachhead market. It gives shipbuilders and operators a way to comply without betting everything on what’s next.

Methanol won’t solve everything. But it buys time without freezing progress. It allows the sector to comply, experiment, and decarbonize — without waiting for every variable to be resolved. It’s not a final solution — but it’s one the industry can actually act on now.

But is this a bridge toward better fuels, or a path we won’t backtrack from? Time will tell.

The methanol-vs-ammonia split has consequences beyond shipping. Every methanol-powered ship nudges the system toward greater CO2 sourcing, tighter biofuel competition, and deeper reliance on synthetic carbon pathways. If it pulls too hard on limited biogenic feedstocks, it could drive up costs for sectors like bio-SAF and biodiesel — and that, in turn, could accelerate investment in synthetic alternatives.

By contrast, if ammonia gains ground — especially blue ammonia from natural gas — it eases the pressure on biogenic feedstocks. Biofuels stay cheaper longer. And green hydrogen projects may look less urgent, and even less profitable.

What fuel shipping chooses next doesn’t just shape maritime emissions — it influences timelines across the energy transition.

Methanol might not be the endgame. But it’s shaping the present. And right now, that’s what counts.